Project: Redactor 📄❌👀

- Elevator pitch:

- Do you need to redact info from an image? Just use paint, right? What if you need to redact hundreds of images? Let's automate that...

- Technologies used:

- Python PyTorch

- Repo:

- github.com/cbosoft/redactor

- Status:

- Released

- Tags:

-

software-dev projects ml Python PyTorch

Motivation

In my day job, I use image data to train machine learning models used in the pharmaceutical industry. As you can imagine, the pharma companies are pretty itchy about sharing company data (especially information about the molecules they’re working on). To facilitate sharing of data, I put together this python package to detect and remove text from a given image. This package was intended for this specific purpose, but the package has applications elsewhere: remove license plate information from video frames, remove identifying information from images, and so on.

Challenges

Redacting Images

The main idea is to cover sensitive textual information on an image. This would be achieved by finding that text, and covering it by a filled white or black rectangle. How should the text location be determined?

I could have made assumptions about the position of the text and just put a rectangle in a set location for the images. This is a weak assumption, and boils down to manually deciding where the text is on the image.

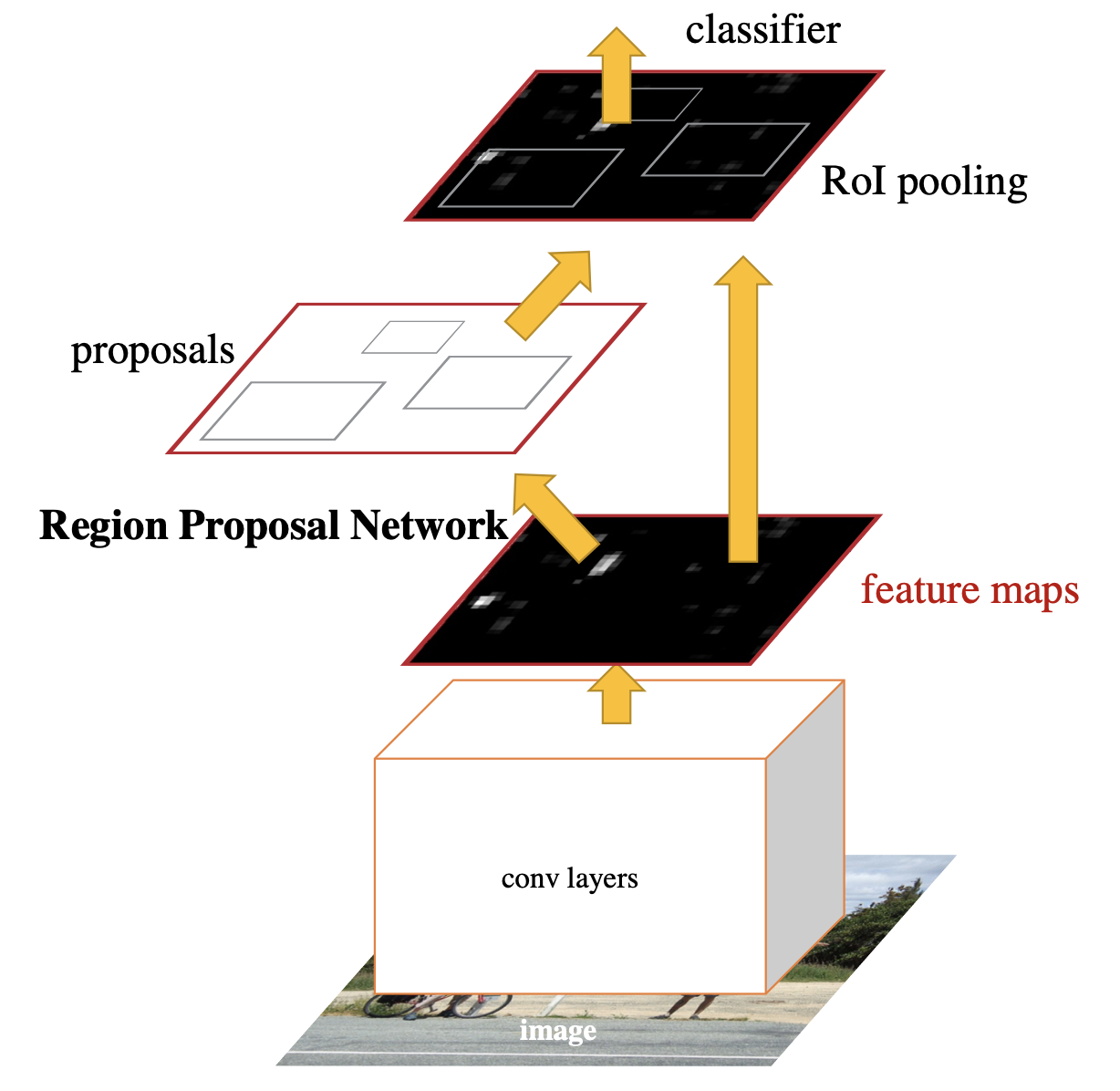

Faster R-CNN Model

Faster R-CNN ModelI settled on using the Faster R-CNN machine learning model to detect the text on the images. This model, developed by Meta AI (née Facebook AI Research, FAIR), is adept at locating (and classifying) objects in an image. It regresses out a bounding box - which can be used here to give the location of the required “redaction box” to be added to the image. The class output would be used to identify what the object is (e.g. if it is a banana or a clock or a dog or a …) but is not so important for my purposes.

Handily enough, the Faster R-CNN model is implemented in PyTorch already. So all I had to do was wrap the model and get some training data!

(Auto) Annotating Training Data

Training the model for this application required images (ideally microscope images) with text of known location overlaid.

One option would be to take images with text overlaid, and then manually annotating the location of the text (using a tool like CVAT). To get a large amount of training data, I would need to annotate a large number of images. This route was immediately nixed as annotation is my least favourite part of machine learning as it is both mind numbing and time consuming.

Another option would be to take an image (with no text) and add text to it in a known location. If done manually, this would be as infeasible as the previous proposed route. However, we can automate the addition of random text to an image. This is the route I went with as it allows for near-infinite training data by adding a random number of random strings of text to previously non-annotated microscope images at a random position.

Open image datasets

Got the data annotation methodology down, now what about the raw images?

I wanted to be able to share this project and in a usable state (i.e. I wanted to be able to share example results, and trained model states). Therefore, I chose to seek out open datasets of microscopy data.

Kaggle is an online platform for getting to grips with machine learning. In pursuit of this, they host many tutorials explaining how to do ML. They also host competitions to see who can get the best result on a dataset and is a great test of learning progress. To facilitate their competitions (or perhaps just to facilitate ML practice), Kaggle host datasets that are free to use and browse (normally requiring author attribution in return). As it happens there are a couple of microscope image datasets up there:

MARCO image from Kaggle

MARCO image from Kaggle- MARCO - a dataset put together by multiple international institutions, consisting of tens of thousands of images of protein crystals. This is curated by the University of Buffalo, main site here. These images sound like a good fit for my purpose, but the images are qualitatively distinct from my target application.

- crystal-microscopics-images-and-annotations - a dataset of microscope images of crystals, perfect for my application.

Training Models

The models are trained using a simple script I’ve developed for training many other models (see my Mask R-CNN training script for another example of the training method). This training script is nothing particularly special: trains for a set number of epochs, in sets of batches. After each epoch, a validation step is undertaken where the model is tested on data not seen during training.

The most novel part of the training method lies in the Dataset object - the automatic and random annotation of the raw images gave a huge array of training data, allowing training to proceed with very little required effort.

Deployment

Once the model is trained and the script is ready for passing on to others - how do I ensure it is simple enough to use?

One of the big struggles I have faced with creating utilities like this is deployment or packaging. Python is fantastic, but there are myriad bugs introduced simply by everyone using different operating systems, different versions of said OSs, different versions of python, several concurrent versions of python, or different versions of the libraries installed. Although this rant belongs elsewhere - I’m avoiding these issues by targeting Python >3.6, and recent-ish installs of PyTorch and Numpy.

Another main struggle is user experience. As, functionally, a solo developer in my institution, if I create a utility I need to maintain that utility and provide user support for it. To minimise required effort at the outset, any utility needs to have two things: good documentation, and a simple interface.

For simple deployment I rely on git getting the code to the user, while trained machine learning models are distributed as zip archives containing configuration information linked to a set of trained model parameters. The main user entry point to the package is a single script redact.py which the user can edit to change any options. I chose this manner of interface instead of e.g. a command line interface on purpose. Typically, I find people running python not from the command line, but from within an IDE like PyCharm or Spyder. These are set up to run a script at the click of a button, so it makes sense to provide this button. In addition, the user is encouraged to copy the redact.py script before editing - these run scripts therefore act like configuration files. Each file contains information on how a redaction was performed, resulting in an easy way to repeat the redaction if necessary. This philosophy is better applied elsewhere to in-silico science (as described in the YACS readme), but could be useful in this context of redaction too.

Conclusions

In this post I have discussed my development a relatively simple (but also somehow overkill) script to detect and black-out text on a given set of images. I described the challenges I faced, and described how I overcame them.

This was quite a successful short project. I have deployed this to some colleagues for testing (August 2022) and may receive feedback, in which case I will update this post.