Electric Vehicles aren't the only solution 🫒🛢️

25 Jun 2023What’s with all the electric cars?

Climate change is a thing. It’s caused by humans: we alter the atmosphere by introducing greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane. To minimise damage, we’re moving away from burning fossil fuels and to other energy sources such as renewables.

Wind turbines provide a renewable source of energy. Getty Images via BBC

Domestic transportation personal vehicles chiefly use internal combustion engines (ICEs). These engines burn a liquid fuel to drive pistons with the expanding gases (carbon dioxide amongst others). Electric motor vehicles (EVs) are being pushed as an eco-friendly alternative. These using batteries to store electrical energy which drives DC motors for propulsion.

No exhaust fumes! That’s good. There’s also lower maintenance needs with an EV, fewer moving parts means less things to wear out, lubricate, and replace.

There are some issues with EVs. The current battery technology - lithium-ion batteries - requires problematic metals such as cobalt and nickel in addition to the obvious lithium (utmel.com).

At a lower stakes level, there are issues with infrastructure. People with driveways have no issues, they can charge their shiny EVs from there - stretching a cable from their house, if not mounting a charging port into a garage. People without driveways don’t have that luxury. At a stretch, a charging cable could be routed over pavement to the car. People in flats have no such luxury. Solutions such as charging points in lamp posts have been floated and implemented. These don’t address high-density living situations.

For some, the kicker is that the electricity to power electric vehicles may not necessarily come from carbon-neutral sources. We’ve only moved the problem, not solved it. Of course, it is easier to generate renewable energy and pump it into the grid to charge vehicles, than to directly power a car with a wind turbine. Moving to electric vehicles would not be a complete solution, but one part of a move to net-zero.

On a personal, selfish, note: I don’t like automatic cars and don’t want to give up my manual gearbox. EVs don’t have even slightly similar drivetrains to ICE vehicles, and only have automatic gearboxes.

Why are we radically changing our infrasture, when there seems to be a simpler solution?

Fuel from olives 🫒

Hydrocarbon fuel is not necessarily bad. Putting particulates aside, the main harm to the environment lies in releasing previously captured carbon into the atmosphere. What if we had a source of hydrocarbon fuel that didn’t rely on extracting oil from the ground? We do - biodiesel!

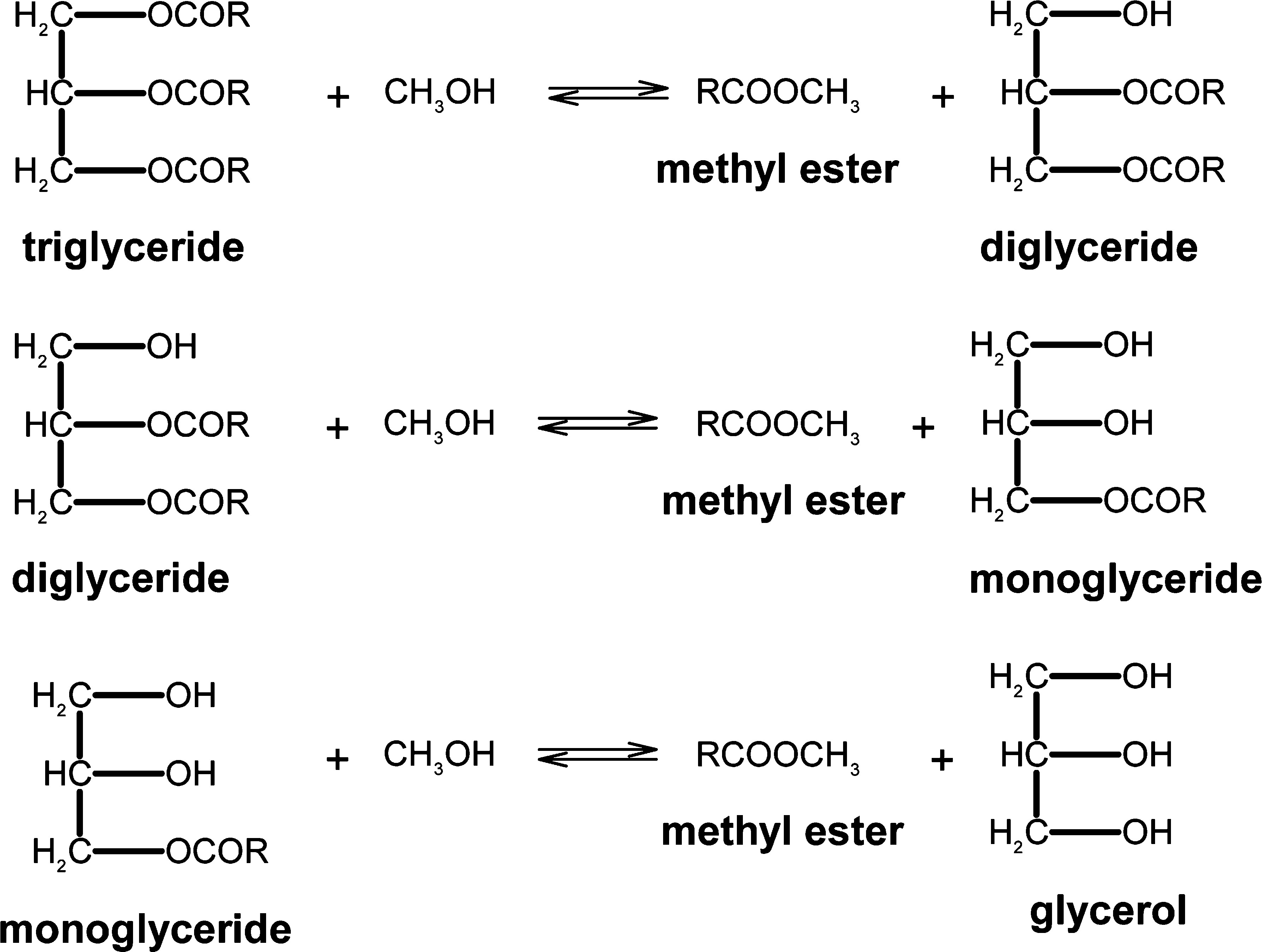

Biodiesel is typically produced from catalytic trans esterification of triglyceride oils. A nice sustainable solution is to use waste cooking oil as feedstock - needing to be filtered and cleaned before turning to diesel.

The advantages of using biodiesel: no (new) carbon released into the atmosphere when running ICE vehicles, while requiring no changes to the infrasture. Fueling up a bio-diesel car would be instantaneous in comparison to an electric vehicle, which would be nice. There are disadvantages of course. ICE engines don’t just spew carbon dioxide, but products of partial combustion, sulphur dioxide, other chemical pollutants as well as particulate pollutants.

Making biodiesel

Chemical reactions producing of biodiesel by trans esterification. From: A. Zięba, A Pacuła, and A. Drelinkiewicz (2010)

All going well, the chemical reaction equations above say that 1 mol of oil gives 3 mols of diesel, plus glycerol. If we are optimistic we can achieve yields up to 96% (T. A. Degfie, T. T. Mamo, and Y. S. Mekonnen (2019)). For sake of our argument here, let’s reduce this is a more achievable 85%. This means that 1 mol of waste vegetable oil will give us 2.4 mol of diesel. As an engineer, I’m not happy with these molar values: let’s get this to a nice, practical, mass basis.

Waste vegetable oils, like any natural product, vary a fair amount. Their chain length varies from quite short up to fairly long (12-22 carbon atoms; 18 on average, O.E.P. Tulcan et al. 2008). This gives an average triglyceride molar mass of 932g/mol (if each chain has the same 18 carbon length). This will react to give three Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) products of the same molar mass of 312 g/mol.

Doing some arithmetic yields 1kg of mean vegetable oil produces 1.004 kg of diesel (100% yield) or 964g (96% yield) or 854g (85% yield estimate). Density of mean vegetable oil is around 0.92 g/cm3 (O. Awogbemi, E. I. Onuh, and F. L. Inambao (2019)) and density of mean FAME is lower, around 0.83 g/cm3 (M. J. Pratas et al. (2010)). Volume basis yield is therefore 1.113 litres of diesel per litre of oil (at best) or 1.07 litres for 85% yield. This makes the maths real nice, pretty much 1:1 conversion of waste cooking oil to diesel.

It should also be noted that this process doesn’t require very high temperatures for good results. 50ºC got the team at the Ministry of Innovation and Technology (Ethiopia) their 96% yield (T. A. Degfie, T. T. Mamo, and Y. S. Mekonnen (2019)).

Production volume

Cooking oil is produced all over the world, from a variety of vegetables. Palm oil is the best yielding at about 3.3 tons per hectare, while most other oils are under half a ton per hectare I. Tiseo (2023) on Statista. Let’s not rob the world of their cooking oil, and let’s only use waste cooking oil. There’s bound to be some loss, but much of it is recoverable in principle. Let’s call it 75%. At the moment however, we don’t recover that much. China recovers about 9% of it’s cooking oil for FAME and soap production X. Zhou et al. 2021. The EU reckons they only collect 14% of what they could - and that’s at most 8l/capita/year EU BIA (2023). So we have a best case scenario (75% oil recovery) and a worst-base case scenario (8l/person/year). I don’t even have to continue this napkin investigation for the worse scenario outlined, 8l of fuel per year is clearly not sufficient.

In total, the world produces more than 200 million metric tons (217 billion litres) of cooking oil per year M. Shahbandeh (2023). Most of that is palm oil, with all the issues that accompany that particular oil.

In total, the world consumes about 330 million metric tons (360 billion litres, very roughly) of crude per year. About 2/3 (by volume) of crude oil is processed to give ICE fuel (diesel/petrol/gasoline) US EERE Fact #676, so that means about 192 million metric tons (240 billion litres) of ICE fuel per year and indicates we need to produce that much biodiesel to replace it.

Conclusion

Let’s not abandon the ICE just yet. We have nearly enough cooking oil to fulfill our global demand for petrol, we need to capture and process more. 9-14% of what’s possible leaves so much room for improvement. There are tonnes of carbon-neutral fuel just waiting for us to reach out and grab it.

We can move from fossil fuels to bio-diesel, and diversify the fleet of drivers on the road to EV and bio-ICE. People in flats and high density situations may prefer the fuelling flexibility of bio-ICE, while some short-distance commuters may choose an EV. Sticklers for the old manual gerbaox can remain satisfied with their bio-ICE cars.

I have only talked about road vehicles here, the problem of aviation fuel is still outstanding. Further, I’ve only talked about the common method of FAME production via transesterification, there are new exciting methods which may produce higher yields, higher energy fuel, and from cheaper feedstock. One group have produced high energy density fuel suitable for aviation using bacteria (P. C. Morales et al. (2022)).